Documents Infield

a solo exhibition by Sanaz Sohrabi

opens Saturday October 7th, 2017

exhibition reception October 7th, 6pm-Midnight

opening reception video screenings at 7pm and 9pm

@ Coco Hunday, 212 W Thomas St, Tampa, FL 33604

Sanaz Sohrabi (Tehran.1988) is an artist, educator, and interdisciplinary researcher, currently pursuing her doctoral studies at the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University. Sohrabi looks at visual traces, acts of viewership and their reciprocal (dis)(re)appearances to investigate the impermanence and malleability of archival records and historical narratives. Performing history via memory and animating the pace of memory through destabilizing the residual archives, have been at the core of her curiosity, practice, and writing. She received her BFA from University of Tehran, and MFA in photography, video and interdisciplinary studio arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Awarded residencies include SOMA Summer School Mexico City(2017), Est-Nord-Est résidence d’artistes(2016), Vermont Studio Center (2015) and Chicago Artist coalition Bolt Program (2014-2015), among others. Exhibitions, festivals, and screenings include Videonale 16 Bonn, Fiva 06 Buenos Aires (first prize for short film), Halifax Independent Filmmakers Festival 2017, Images festival 2017 Toronto, Transart Triennale 16 Berlin, Expo Chicago 2013, and 6018 North Gallery in Chicago, among others. She co-directs Tamaas online journal on arts and politics, an online platform of non-simulation and public speaking, a space for a declaration of thoughts, desires and where urgencies manifest.

##

##

A Conversation with Elliot Reichert (Chicago) and Sanaz Sohrabi

EJR: Let’s start with your recent work, how did you arrive at those particular monuments? There is some geographic continuity between them—Georgia, Turkey, and Armenia—but I am sure there are others you could have selected. How did the research process take you to these places?

SS: I’m a news hoarder, I read the news all the time. I look for what images get circulated. In the case of the first video, there was an article on BBC, titled “The Monuments That Were Too Much To Bear.” There were six different monuments that were moved or destroyed because the general public couldn’t tolerate them or because there was a local consensus that the monument had a tension with the surrounding space or for other political agendas. I was struck that an image can be reproduced in a sculpture and that sculpture can be again mediated through photography, creating all these layers.

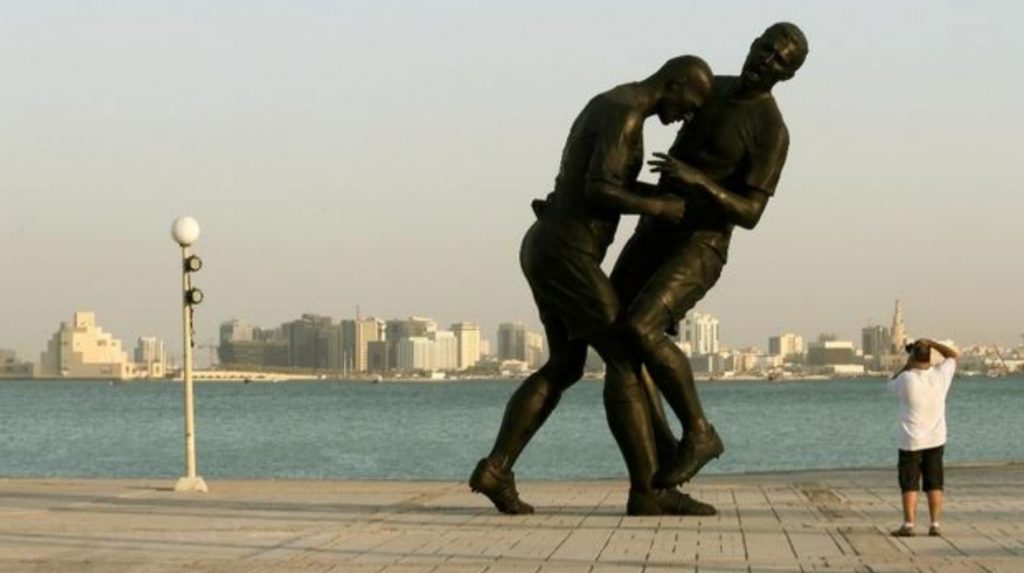

For me, it’s a process of comparison, a process of the psyche. I have this folder that I constantly collect photos in, and have been doing this for years. When I do a project, I always go through them and look at them. This time, I saw the photos of Zidane and by chance I also saw Naser al-Din Shah, King of then-Persia for almost second half of the 19th century. I thought, How can Zidane and Naser al-Din Shah become these figures that I associate with certain political and cultural personas? They hold an aura, in France and Iran both. They both have a cloud around them.

My research is about images, and images become containers of certain stories, of spaces, of bodies, of characters, of events, which gives me an opportunity to open things up. And the same thing, before knowing the monuments in Armenia and in Georgia—my starting point was Mehmet Aksoy’s Statue of Humanity in Turkey. I knew about it through the 13th Istanbul Biennial. I saw the photos of Wouter Osterholt’s project Helping Hands (2013). During the removal process of the monument, the artist made a really large handmade out of concrete. He would put the hand on a cart—I’m not sure the city, maybe it was Kars—and move it through the city and ask people to talk about their feelings about the removal process, the presence of public monuments, and about the hand that the artist made. He asked each person to make a gesture with their hand, and they would cast their hand in plaster. Then he collected all these hands gestures cast in plaster and the concrete hand and temporarily installed them at the bottom of the monument before it was removed. So, this project was my introduction to this monument in the first place.

I’ve always found that monument to be fascinating, and I happened to be in Turkey that summer and I knew I wanted to see that site and see Kars.

For me, it was really interesting finally to see the place, because of the 1921 Treaty of Kars and its following histories. There were other places I wanted to see, and for me it was interesting to not only focus on one place but put one place—one image, one event—next to another event to create better understanding, to let the whole thing breathe.

I knew there would be something more in this region, with all the events that have happened in the past two hundred years alone. With the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828, part of Armenia and part of Azerbaijan, which were part of the Persian empire at the time, were given over to the Russian empire to settle the Persian-Russia wars.

Another point of entry is a different image. It is a photograph of a diplomatic gift exchange from 2015. Viktor Orbán is the current Prime Minister of Hungary and an anti-immigrant, anti-Semitic maniac. His party is one of the reasons the Central European University is on the verge of being closed. But he gets along with the Iranian state pretty well. So he brought this gift, which was a big, framed map from the National Library of Hungary, and it was a really peculiar thing to bring as a diplomatic gift. In the media in Iran there was a lot of sensation about it. They said, “It is such a good gift. It shows Iran in its glory.”

EJR: So it was a map of Iran, in its most extended form, as the Persian empire?

SS: It was treated that way in the media, but I was intrigued and so I found an image of the map. They said it was Iran in the 1840s, but by that time, Iran had already lost a lot of its territory in the north; it was already shrinking. The map, I think, was from the 1730s, and it wasn’t Iran or the Persian empire at the time, it was a combination of the Persian, Ottoman and the Russian empires, as well as some parts of the Arabian peninsula.

I was interested in how this representation, this map, got picked up by the media and was narrativized. And that was part of the reason I wanted to go to this area. And I could travel to Georgia and Armenia even with my shitty passport.

EJR: That Iranian passport is good for something, I guess. It’s interesting that that area, which is being ascribed to the sovereignty of Iran in media, is accessible to your passport, which itself has a much smaller travel footprint, and yet you are able to move through those spaces.

SS: In Tehran, I see how the urban space becomes a contested area through different public projects that are directed at the figure of the citizen, of the viewer. The city is very aware of your presence. There are points in the city that are there for you to view, to observe and to form some kind of subjectivity, whether that’s through mural paintings, altering the squares with different sculptures and public installations.

EJR: In Ramallah this summer I saw a project by Behzad Khosravi Noori and Benji Boyadgian at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center called Around About (2016). They made a video and installation about a roundabout in Tehran that contained a monument to the Palestinian resistance. Do you know of it?

SS: There are quite a few monuments attributing to the Palestinian resistance in Tehran. We have a Palestine Square in the city center.

EJR: I think it was at the square, with sculptures of the fedayeen.

SS: Yeah, there’s a Cinema Palestine in that square which is a very cool hub actually in the city center.

In Tbilisi, Georgia, there was this Soviet monument, “Andropov’s ear,” that had been removed. Nothing else had been built on it, and it was in the central part of the city. I find that structure quite fascinating. In Tbilisi, there are a lot of transformations going on because in Georgia there is a lot of pro-European Union sentiment. I haven’t been inside of the European Union recently but in other areas, like in Turkey, you only see Turkish flags, but in Georgia they are everywhere. In Georgia, there is a lot of anti-Russian sentiment.

More so, I noticed in the Georgian National Museum, that there would be labels for objects from the 3rd or 4th century saying: “And at that time, the glorious nation of Georgia…” It’s fascinating to see how these nation-making narratives occur in museums and public space.

EJR: All of the monuments in the more recent film mark a transition from one state power to another. It is interesting to think of Georgia now gravitating toward the EU as a regional power, almost an imperial power, to stave off a Russian influence, perhaps?

SS: I’m not an expert in Georgian politics, but to give a small preview, for instance, George Bush is very popular there. There is a highway named after him.

EJR: George, George Bush?

SS: Yes, because he supported them during the war with Russia. I know these things now, but I didn’t then and they are not a part of how I made the work. I went there thinking that I would work with the public monuments that had come up through my research. I had spray paint, and I thought “I’m going to go, and I’m going to mark every monument that I see and alter it.” I was going to do pockets of installation and in-situ performative actions. I move a stone, I document it. I see a shadow, I spraypaint and I document it.

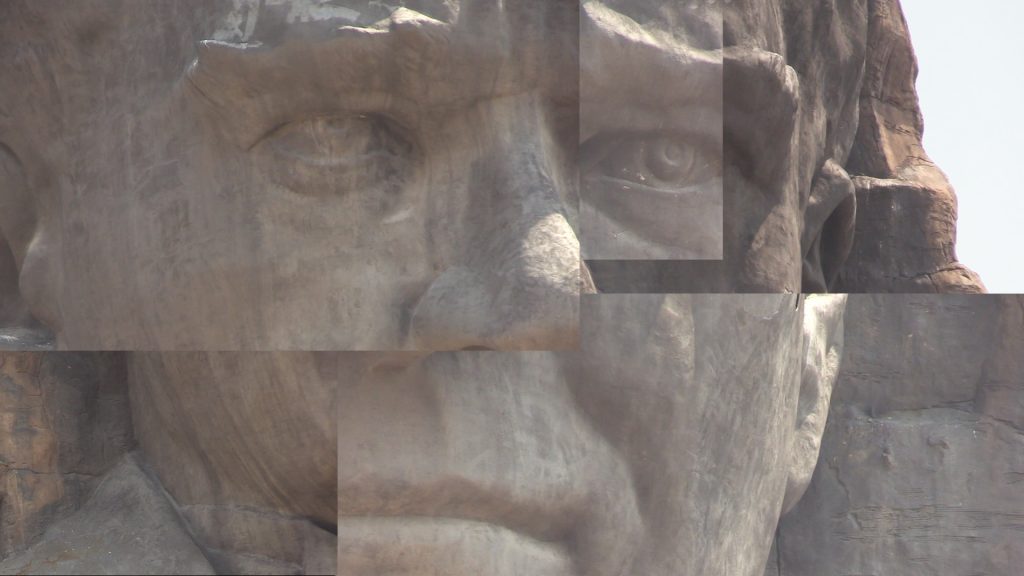

It was kind of ridiculous, but I have footage of painted shadows by the monument in different locations throughout the filming and I may use them at some point. Some of it turned out to be interesting. I went there with so many ideas— I’m going to be drawing lines with paint, moving stones and objects. I’m going to intervene in the spaces in between as I visit the monuments. In the end, I included some of the monuments that were not part of the project that I just encountered, like the face of Ataturk in the mountain in Izmir. I didn’t plan to visit that, I just saw it on the way. I had maybe ten or twenty hours of footage that came down to seventeen minutes in editing. It was about observing the entire time. In a way, the camera becomes a limb of the body.

EJR: So you were shooting constantly as you performed these interventions that ended up not making it into the work. And you came to those monuments, those three points, afterward?

SS: I went to those three places in particular, but during the process of writing, of editing, I thought that those moments made sense together. In the visual essay, you need breathing spaces. You can’t just go full force. It’s not an educational video. It is factual to some extent, but it has to have space for contemplation.

I started writing the narrative after I came back. I had all the footage and I ran through it. Instead of keywording, I key-imaged the film to bring together the images and connect them. From there, I began editing. The first cuts looked so weird. They were nothing like what became of it. I had all of the spraying in it and I realized that they really didn’t need to be there.

EJR: It sounds like you’re capturing these images and then sifting through them as if they were a part of someone else’s archive, as if you were a researcher of your own material.

SS: Yes, and I wasn’t upset that so much footage did not get used. I’m going to use it for other projects. It’s limiting, in a way, not to have a storyboard, but for this project, I went in with a thesis. The narrative came later, through the editing.

EJR: But with the Zidane video it was, in a way, about contemporary art, or at least the work of a contemporary artist.

SS: Yes, Jeff Wall. Not a big fan though!

EJR: Ha! I was thinking about Abdel Abdessemed, but yes, you discuss Wall too. What don’t you like about his work?

SS: Photographs age, and I think Jeff Wall’s photographs have not aged well. They don’t work anymore. I once read in an article that he categorizes his images as documentary; neo-documentary, which are the reenactments; and cinematography. I think when you are trying so hard to make your work a qualitative assessment of reality by surpassing it, there is this danger of the work not keeping up with reality. Our perception of reality, especially with regard to photography, has changed. Photography in its inherent qualities have not changed, I think, our perception of it changes. He tried to surpass the real, mocking it in a Baudrillardian way, but his photographs have not been able to keep up, let’s say after three decades. Those lightboxes have not aged well, I think.

EJR: These two pieces of yours are both documentary in a way, as you are telling research-based narratives, but they’re not documentaries and they are not hyperreal in any way. You’re researching a history, creating new images of that history with the help of archival images, and you’re helping people understand these stories in nonlinear forms. It would be interesting to see you apply your research sensibility to the documentary mode.

SS: I’m really interested in having a multi-channel installation that brings together documentary and fiction into space, but it’s a rough idea at the moment.

EJR: With the Zidane piece, you say that you were watching the live broadcast when it happened. Did you have a sense at that time that that moment, that headbutt, was worth memorializing

SS: Not at all. I just thought it was crazy and it was a big deal that France lost, but that’s all. Harun Farocki has a piece about this World Cup game in 2006 between France and Italy, Deep Play. And also Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon’s Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, which has seventeen cameras from all over the court following only Zidane’s face for the length of an entire game.

EJR: Especially with highly mediated events like that, the image becomes immediately available to anyone and everyone to interpret and to work with. I’m sure there are still others who have worked on this image. The issue of the multiple cameras is interesting with regard to the Abdessemed sculpture, which is such an incredible recreation of this moment. It’s both very dynamic and appears highly accurate. In your video, there is a moment that juxtaposes the footage of the match with an image of the sculpture and the resemblance is remarkable. I imagine that rendering was in some way achieved by having all those camera angles available.

SS: I think so. I showed this piece to my mentor Bavand Behpoor, who is an incredible art historian and just went back to Tehran after finishing his Ph.D. in Munich. One of Bavand’s comments was that Zidane was an embodiment of the invisible presence of Algerians, Tunisians and Moroccans, and other North Africans in Paris and France at large.

EJR: Occupying this highly visible and beloved role as a national icon.

SS: Exactly. He’s an embodiment of many cultural questions. And so was Nasr Al-Din Shah, according to Bavand. Naser al-Din Shah was obsessed with France and traveled to Europe three times. He spent a fortune of the public’s money going to ballets and bringing cameras back to Iran. He was a terrible politician, but an amazing artist, I think

EJR: I didn’t know that Nasr Al-Din Shah was a photographer at all. That self-portrait of him with the women of his harem is incredible. Your comparison with the Jeff Wall photograph is illuminating, but that photo is so much stronger.

SS: Maybe I gave a facile interpretation of the Wall photograph?

EJR: I thought the Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) made a lot of sense, but I was also thinking of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656). Those are both well known images and certainly influenced centuries of art, even up through photography.

On a different note, I saw the Abdessemed sculpture at the Pompidou, but I didn’t know that it has this afterlife in Doha. Those images that you printed out of it being taken down and traveling are compelling. At one point, when the sculpture is on the back of the flatbed truck, it looks like they are embracing, like they are having a moment of intimacy that is far from the violence that is being memorialized. And in the Monument to Humanity in Kars, there is that hand reaching out in a gesture of togetherness.

SS: Perhaps. There are a lot of instances of public sculpture being removed. If you look for the monuments to Stalin and Lenin that have been removed in Eastern Europe, you will see plenty of examples.

EJR: And even right now in the States, with Charlottesville and elsewhere.

SS: Exactly. I showed this piece in Mexico City, where they have a problem with monuments. There are too many of them as some friends from D.F. told me with a laugh! There is a monument in every corner. The city has spent a great deal of money commissioning not very well thought-out monuments recently, I was told. And as a result, there are a lot of artists working with monuments—mapping them, tracing them.

Everyone was really positive about the piece in Mexico City, but I didn’t realize that showing it there would have such a different read. In Chicago, you have the Picasso and others alike, and that spatial sabotage by Anish Kapoor, but they take up less space in your head, I think.

EJR: And no one thinks of those sculptures as monuments, they’re just public sculptures. They’re not monumentalizing anything.

SS: Someone once said that the Anish Kapoor sculpture was a monument to…

EJR: Capitalism?

SS: To narcissism.

EJR: That’s effectively what it is, I guess.

SS: In Mexico City’s screening of the film, the audience also asked about the Confederate monuments in the U.S., and this is very complicated for me. If I were to translate what is going on with the monuments in Charlottesville and Louisiana, the same way I did with these three monuments, I don’t think it would work…

EJR: Those monuments were put up at the turn of the century many decades after the civil war in order to assert this fiction of history. There’s something there, but it’s a different story. The idea of taking down a monument in order to forget, this is what’s happening in your video with the Georgian monument during this flashpoint of conflict between Russia and Georgia. And then the Monument to Humanity, which is taken down because Erdoğan and the rest decide that it’s no longer acceptable to have some kind of reconciliation with Armenia. Not that a monument could even do such a thing, especially one that is erected on land that some consider to be occupied. But you end with the monument in Armenia, the transformation from a statue to Joseph Stalin to Mother Armenia. It seems almost hopeful, in case of Mother Armenia, because it is the only of the three where a monument is not just destroyed, but replaced.

SS: I didn’t necessarily think about it as being hopeful. It made sense to end it there because Ii is a site that is still active and generates and keeps memories and images. That monument itself is really interesting. It has such a presence—you really can see it from almost anywhere in the city. Yerevan does not have a lot of those terrible skyscrapers that obstruct the skyline.

At some point, I will go back to Yerevan and focus on its architecture. I found it really mesmerizing. In some ways, it’s similar to Tehran, but also it has a very distinct Russian architecture.

EJR: In both of the videos, you use the term “spatial” to sometimes describe people’s physical relationship with monuments or, in the case of the more recent video, to refer to your movement through these geographic and national territories. It reminded me of a show you had in Chicago called “Spatial Agreements.”

I often think of monuments as markers of time and history, but you seem to also be concerned with the spaces they create. You have these long shots from over hilltops, the movement of the Abdessemed monument from the Pompidou all the way to the corniche at Doha to a storage space somewhere, some kind of negative space where no one can see it. It recalls Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981), which was removed from Federal Plaza in New York City and placed into storage indefinitely after a huge public controversy.

SS: There’s a show up in Montreal now at the MAC (Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal) about the 1967 World Expo. My co-supervisor Monika Kin Gagnon is the co-curator of the show and her work is on archival practices, or what she calls “animating the archives.” She gave us this article by Michael Lynch, in which he compares the Iran-Contra Affair and the OJ Simpson trial as two events that produced different forms of archives—the privileged archive and the popular archive. With the Simpson trial, it was a highly mediated affair that produced its own archive through television and the news. The article was written just after the trial, and it argues that archives are not necessarily objective artifacts and that it makes more sense to do an ethnography of an archive, to use them as material for other practices. How does an image used at a trial generate new forms of information, and what is the afterlife of that image?

I am not doing historiography; I am not providing history. To an extent, I am working with historical facts, but I am more interested in doing ethnography about these events. It’s not about the monument as an objective thing, but about how it is mediated.

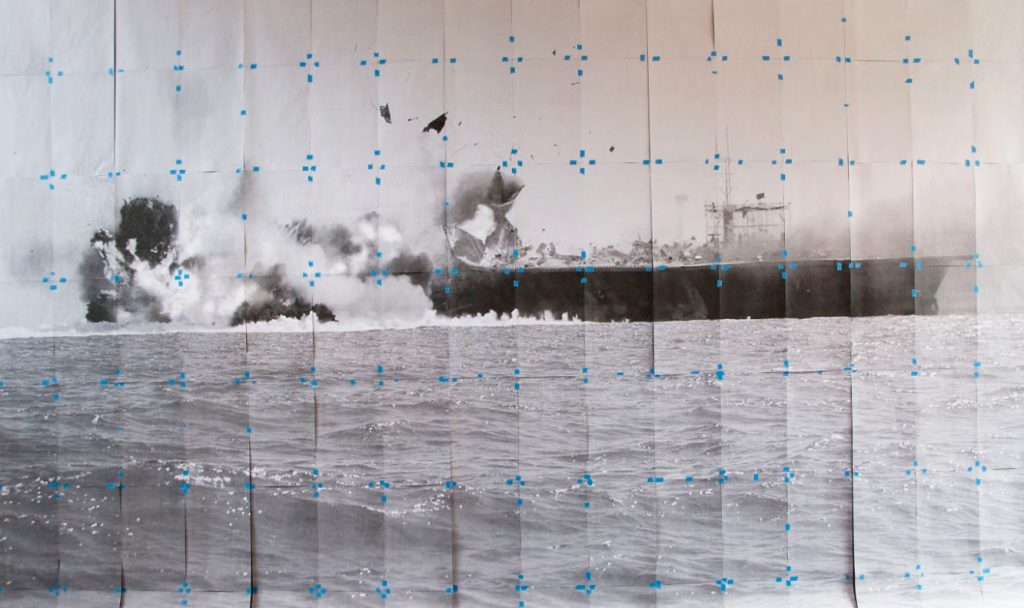

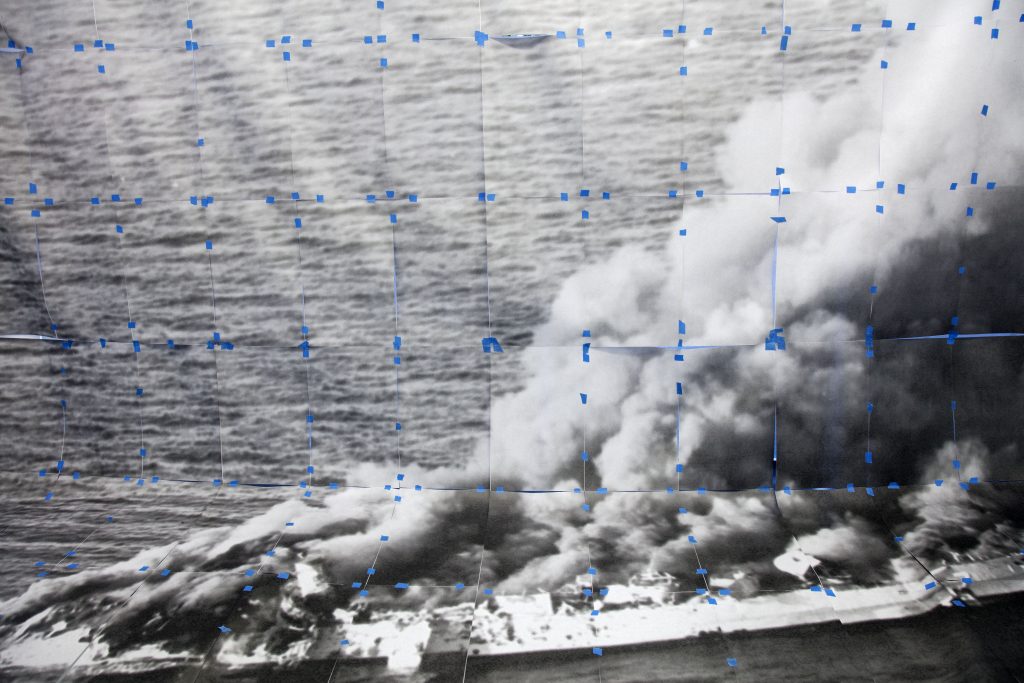

EJR: When you talk about the nonmaterial aspects of the archive and how it can be used in ways that are not historiography, you still have a material component to your work. With the Zidane photos, you are physically manipulating and overlaying them, and with the slide projections in the more recent video, you are indicating points on the images by attempting to gesture into the projection. It seems that you are still concerned with materiality, or immateriality.

SS: I was very wary of this Ken Burns effect.

EJR: I was going to call it the Akram Zaatari effect; lightboxes, manipulation.

SS: Ha! I think it’s more interesting to pin a photograph to something. I was going to do it again with the second video, but I thought to project them instead.

EJR: I wasn’t sure if those were your photos, but the projected images had a much warmer quality visually.

SS: It was a 35mm projector. I tried my best to make the white balance more neutral.

EJR: I thought it made them appear more archival in the way that we expect these materials to age.

SS: Near the end, the photo of the soldiers in front of Lady Armenia, people think that I took that photograph, but it is also found. I wanted to use any photograph available online. There is something about these materials being to some extent accessible. Although it took me a while to find some of the photographs. Some of them would not come up. What you find when you search depends on your search history, the time at which you search, what language you search in—search engine algorithms affect that process.

EJR: Even where you are searching from geographically would affect what comes up.

SS: Exactly. I only recently came across the photo of the moment between Stalin and Mother Armenia.

EJR: One wouldn’t necessarily photograph a monument when it’s not there.

SS: Actually, I found this essay in an architecture journal that described the lack of documentation in the removal process, and the author speculated on the many photographs of the monument that might be found in family archives.

EJR: Public archives like the internet and personal archives, all of these photos linked by this one monument that are inaccessible to you.

SS: If my job were a historian, I would go to Yerevan and go to an architectural society or a library, but this video did not demand that. Or, maybe it did and it does not have enough accuracy.

EJR: It’s not a question of accuracy. You’re not a historian, at least not yet.

##

Elliot J. Reichert is a Chicago-based editor, critic, and curator. He is Art Editor of Newcity and formerly Assistant Curator at the Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University. He is currently pursuing masters in the departments of Art History, Theory and Criticism and Arts Administration and Policy at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His research concerns state-formation and nationalism in the modern Middle East as it manifests in the research, display, and transformation of cultural heritage.