a solo exhibition by Michael Cuadrado

opens September 4, 2021, 6-9 pm

304 w Crest Ave, Tampa, FL 33603

masks required

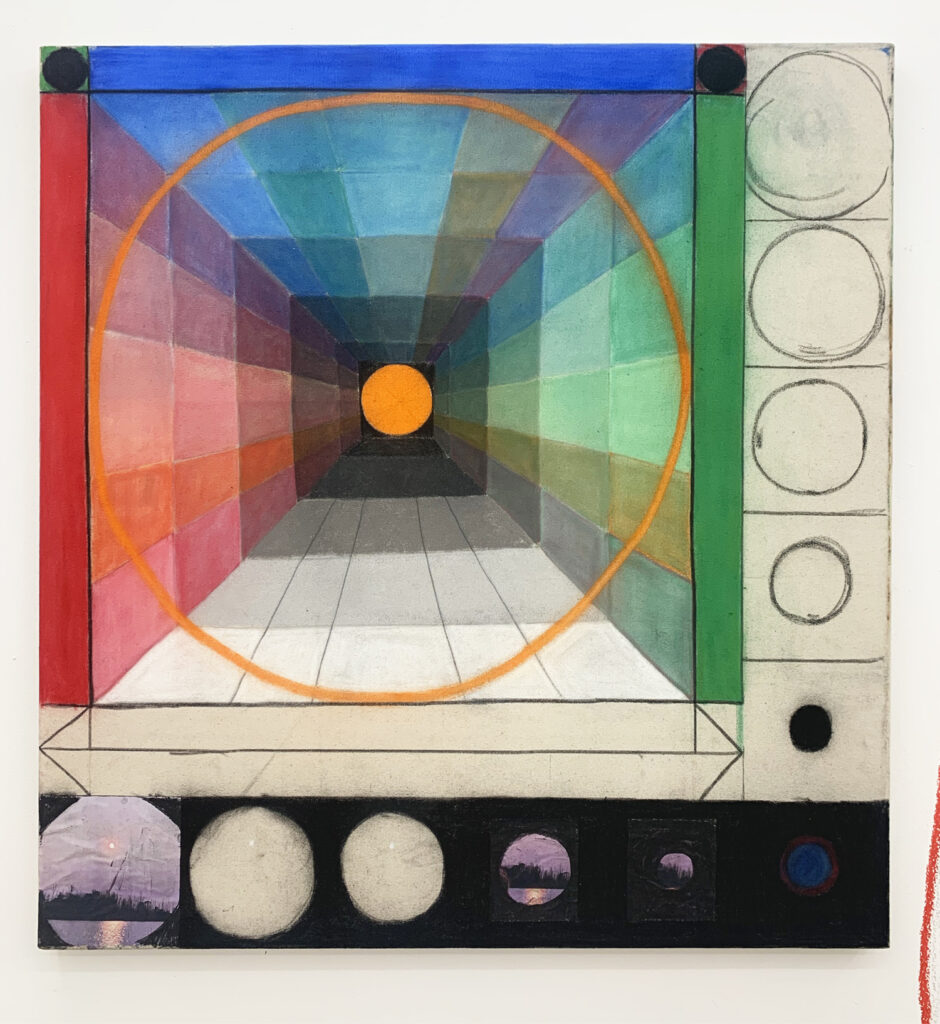

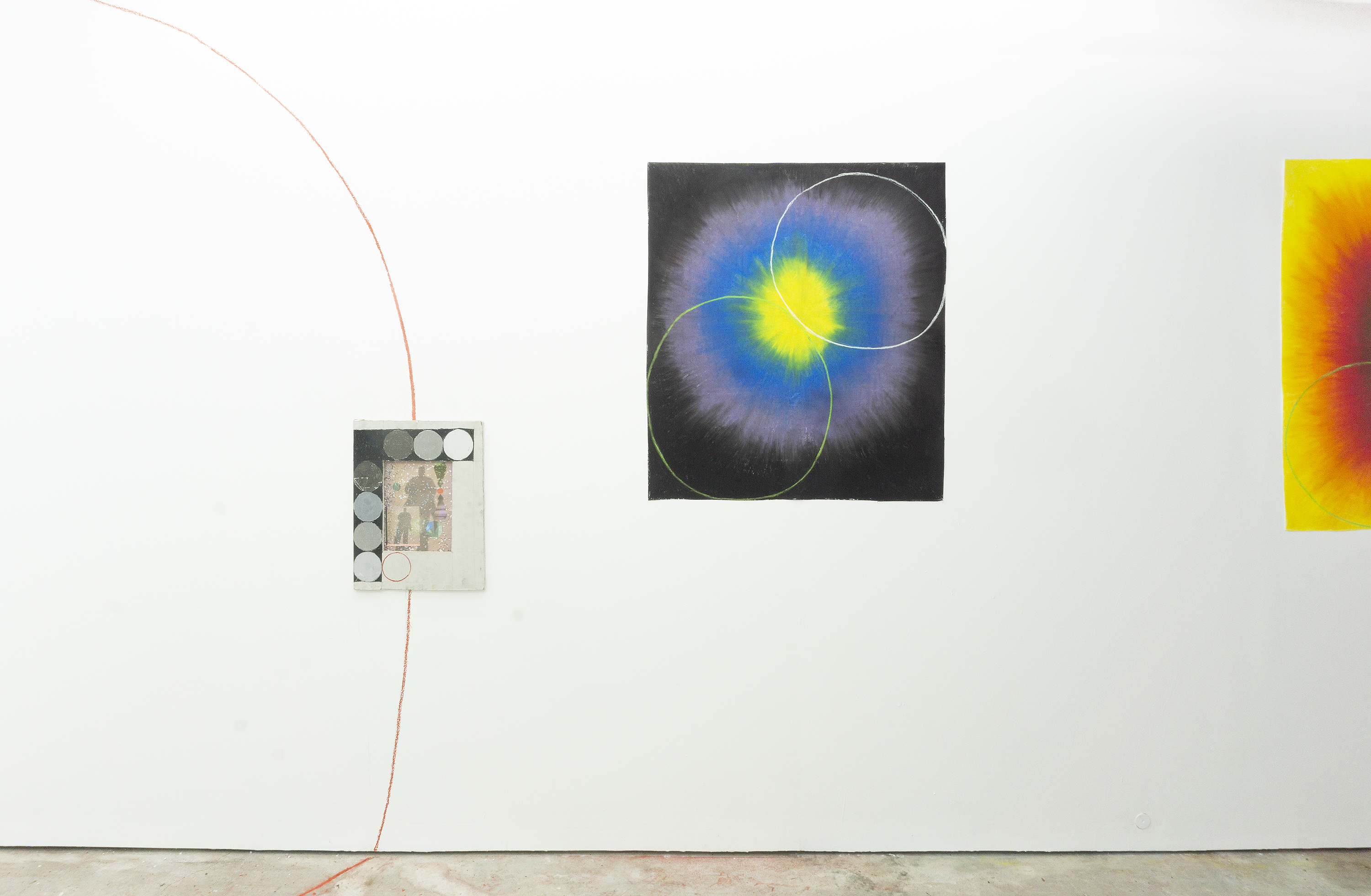

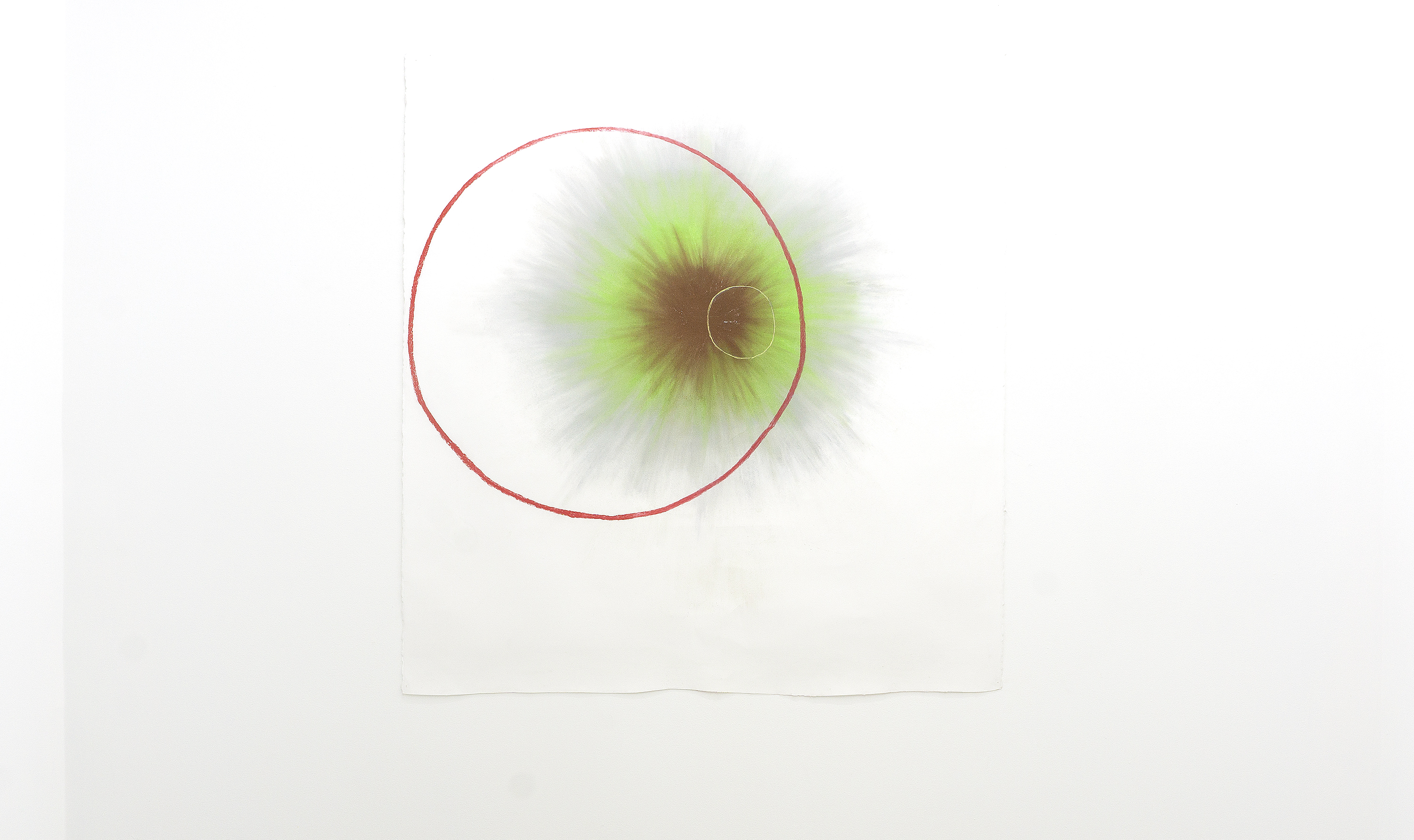

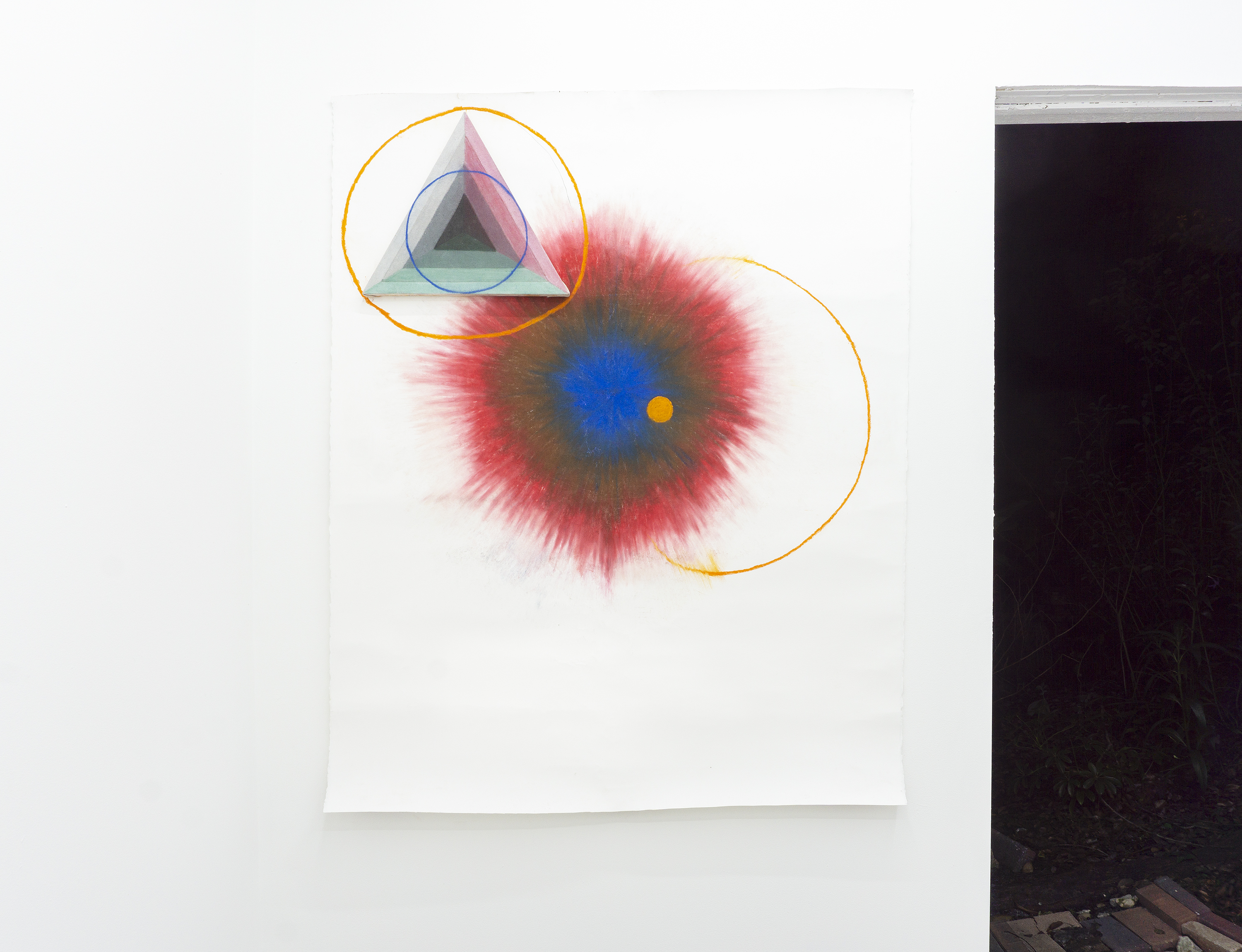

Coco Hunday is thrilled to present Two Slow Dancers, a solo exhibition of new works by Michael Cuadrado.

“At large, my practice considers longing and desire in relation to queer and Latinx subjectivity. Largely influenced by Sara Ahmed’s book “Queer Phenomenology,” Frantz Fanon’s “Black Skin, White Masks,” and “Semiotics: The Basics” by Daniel Chandler, I have turned to astrology, religion, logic, science, and mysticism to help answer the question: How should we love? If there were a manual on queer love, what would it look like?” —Michael Cuadrado, 2021

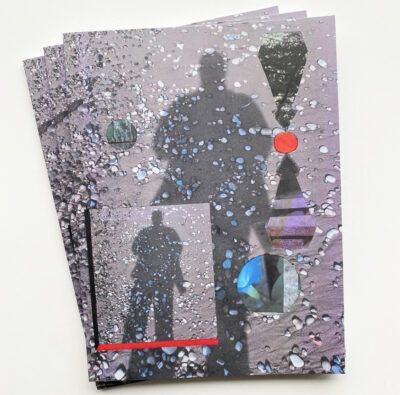

For Two Slow Dancers, the gallery collaborated with Matthew Leifheit/Matte Editions (NYC) to publish a catalog documenting the exhibition, featuring a conversation with critic and theorist William J. Simmons (released in the spring of 2022, 20 pages, 6×8″)…text of the interview after documentation down below.

Michael Cuadrado was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, raised in Florida, and currently lives in Chicago, IL.

In conjunction with this exhibition, Coco Hunday will publish on its website the PDF proposals of over 200 open call applications received alongside Michael Cuadrado’s original application. The original call for submissions can be found at OPEN_OPEN_CALL.

further documentation and prices upon request:

On the occasion of the exhibition Michael Cuadrado was interviewed by critic and theorist William J. Simmons:

William J. Simmons: I’m really glad that we are in touch, because I think this work is really interesting, and I think the way that you talk about it is really interesting too. And on that topic, in your artist’s statement, I was interested in your evocation of love, which is not necessarily a term you see too often, because it has sentimental or cliched connotations. But in certain corners of queer theory that I think you’re obviously invested in, like Sara Ahmed, love is a really important term, in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick or Roland Barthes or whatnot. So to get to the question, why this evocation of love? What do you mean by it?

Michael Cuadrado: Why love? I have to mention that all of these ideas surfaced during the beginning of the pandemic. I mean, they were always in my mind, but when things shut down, I was like, “Okay, what?” I felt loss. And I was like, “What is the one thing that’s driving me and the world?” I was in love with someone. And it’s also, you know that film, I don’t know who made it, but it’s the power of 10 or the rules of 10?

They start off really zoomed in, and then it’s 10 degrees, and it gets bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. And it shows the entire world or the galaxy. But it starts off as a couple, and it’s a guy and a girl, whatever. The idea of the couple being the starting point, and then it ends up with a galaxy, I felt like the purpose of life is to find your other person. And I felt like, “Okay, if I am going to try to take on this heavy topic of love, and love while being queer, where do I start?” And I felt like starting at the very basic level of structuralism. I just felt lost at the time, and that helped me find some kind of balance. Does that answer your question? Maybe? I don’t know. Why love?

Can you investigate love while being in love?

I mean, that’s quite literally what happened. Yeah, I think while you’re in love is the best time to really do a deep dive on what love is when you’re right in the middle of it, because you’d try to question things, and at least that happened for me. Where are all these feelings coming from? Why is it taking over my entire existence right now? But if I wasn’t in love, I don’t think I would have had even thought to ask myself those questions. Yeah. I don’t know if that’s a good thing.

The reason I asked that is because something I think about a lot is how queer and feminist theory, generally, is so invested in critique or deconstruction. And critique and deconstruction are sometimes seen as being at odds with loving something. So it sort of begets the question of if it’s possible to love or deconstruct, or if it’s possible to critique and deconstruct that which you love. And I think maybe that gets at how you work. I noticed in your artist’s statement that you mentioned that you are committed to traditional ways of showing work. And so, maybe in a sense, there’s love and critique going on in terms of how you make your work and how you present it.

I feel like my background in school was very traditional. I went to Pratt Institute for school and it was a very, “We’re going to teach you these things.” (Josef) Albers was freshman year. They taught us all these things. And I generally felt like I loved all of that, modernist painters. Then, as I got older, oh, what’s his name? Oh my God. He has the black paintings, and they found these racist-

Oh, Malevich.

Yeah, yeah. So, when you’re young and you don’t know, “Oh my God, beautiful.” Or at least I was like “Oh, I love this.” And then I was like “Oh shit, here is where things start to get complicated.” You have to ask yourself, “Okay, you love this, but you can also be critical about it, because you’re so invested in it.” Which is how I’m trying. I do love painting in a traditional sense, but I also really enjoy trying to critique that institution, and, “How about I put this circle on the wall?” It felt like a minor gesture, but it maybe wasn’t in the space. How do I skew the way I’m making this work? And also go back to love. I have this complicated thing where, growing up, my family was kind of racist. And I feel like I’ve been really drawn to white, muscular, slender men, and I’m also like, “Okay, it might be time to face that. Why is that?” I feel like they mirrored that. My interest in art and art history and then my desire for men, they’ve somehow became the same thing.

That makes a lot of sense, and I think it’s like that for a lot of people. So then how would you characterize your relationship to painting, but also to other media? Because you definitely engage with other media in your work.

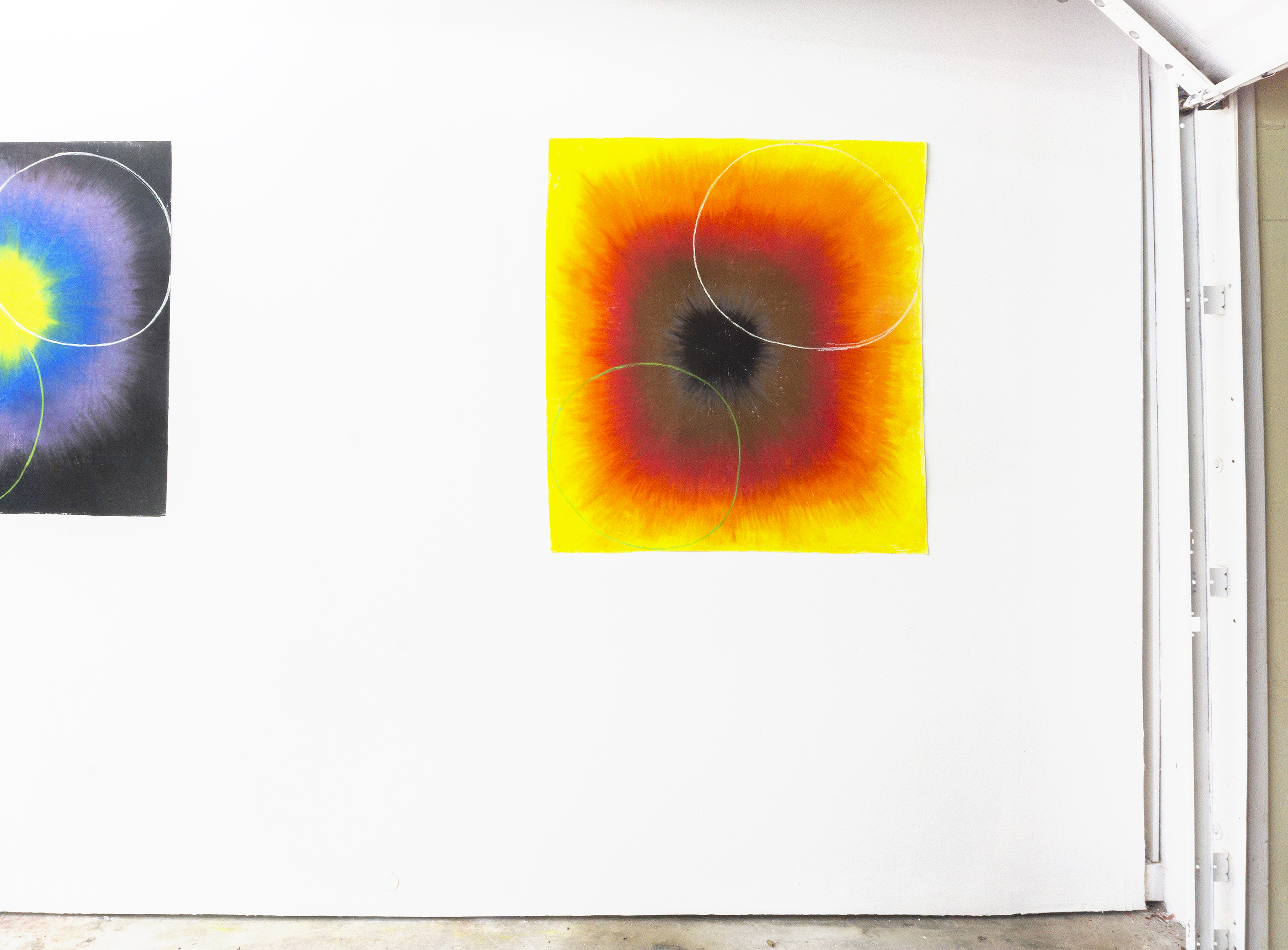

My relationship to painting, I feel like I’ve always tried to somehow engage with painting, either with the material, or historically, the topics that are being painted about. But also, this is maybe not a big thing, but I don’t actually use paint. It’s all chalk, pastel, or charcoal. So I’m trying to mimic the use of paint with this other medium, although, if I didn’t tell someone, they would assume it was paint. So, maybe it doesn’t really matter, but I feel like there’s some kind of coding going on and how I feel about painting. I’m here for it, but I’m also not here. I’m trying to get by with other ways of making that are potentially sneaky or something. Maybe it’s not that sneaky.

Yeah, and growing up, the idea of being a painter felt like such an academic, “Oh, we don’t do that as people of color. But why are you going to art school? That’s not a thing that you do.” And I was like “Well, it could be a thing that I do, and it doesn’t have to be a higher thing.” But that’s where I’m trying to fit myself within painting. I am super into the academic and theory part behind painting, but I’m also into the real aspects of being a person and expressing that through these modernist or minimalists marks or forms. So I feel like maybe they’re not always talked about.

It makes me want to ask about theory, because you mentioned it. I thought your interest in Sara Ahmed was worthy of note. And so I wondered, what resonates for you about Ahmed’s work?

Yeah. I’ve been reading that book for over a year now. I think she’s able to talk about this topic in almost such a broad way that I’m able to understand it and then maybe bring it down to my own. So a lot of the work mostly comes from when she talks about objects and objects in space, and how to clear the space, and what directions mean, and the meaning of the word direction and how she says if you give someone a direction, it’s like going from point A to point B in a straight line, and the idea of following a certain path or clearing this path or whatever, I really loved that. And it was easy for me to take her theories and make them my own theories about this guy that I was seeing. It felt like I was reading this book and putting me and this person as the objects that she was talking about. And also, because she’s mixed. She’s white and Arabic, I think? And she talks about that too, towards the end of the book. And this is a whole other thing, but Puerto Rico has a ton of people there who are white people, black people, and everything in between, and I don’t even know what I am, and I felt this similar feeling of being potentially mixed race, and how to position yourself in the world as someone who is mixed and queer and you’re not sure of things. I don’t know. I just really appreciate that she did want to talk about emotions and all these things in a theoretical way, but also not too far, not too above me.

So, what I took from it is, if you’re going through a break up, it’s not what she’s saying, but from me. She says “When you first get a hammer,” I mean, and if you know this, sorry to tell you again, but she says, “If you have this hammer, and the hammer is a perfect hammer, and you’re using it, and then suddenly the hammer becomes too heavy for you to use, and then the hammer is a useless object now.” And that analogy fucked with my mind so much. It feels similar if you’re dating someone and then suddenly things turn bad, “Oh, this hammer is no longer useful.” And how to come to that point and what that looks when that happens. Yeah. And you mentioned actually, I have the book here, but I read this a few months ago. Oh my God. Also obsessed with Roland Barthes, so I was like, “Yeah.”

Yeah. He’s the saddest, the gayest. The gayest, saddest theorist.

It’s so sad.

I mean, actually, fun story. Well, not fun, but one of my professors knew him and Simone de Beauvoir, because she did her, it was back in the day when you were like, “Dude, you’re on a Fulbright, and you went to France and you just found Simone de Beauvoir.” But I guess she told me, so Barthes got hit by a laundry truck, and then it started this long decline for him. But she told me that she saw him get hit by the laundry truck, which-

That’s very sad.

Isn’t that sad? And such a weird historical happenstance. But anyway, I think this point about applying theory to one’s, everyday life is important. And I don’t know, I guess one thing that’s interesting about art, and interesting also about what you said, is I guess the realization that as we get older, things change, that a lover or a boyfriend or a parent or whatever, that you might not always be aligned in the way that you want to be. And I think that’s really interesting and important.

Yeah. I mean, saying parent, yeah. It’s family. Yeah. I think so too. I mean, hence why I was moving to a new city or state when I was able to leave my household, but I’m not trying to be sad about it. It’s just a matter of fact thing. All right, here’s this moment in time where I’m no longer aligned, like you said, with these people. So how do you start from scratch if necessary? And these theories helped me understand where I stood in relation to other people who you’re once super aligned with, and they’re not anymore. But yeah, Barthes, I mean, so sad, I cried so often, but just the way that he’s able to make every fragment another step to recovery. But it’s so real, that feeling when you think you’re just falling in a black hole. But yeah, I don’t know. I could go on about that book. I think it’s great.

Yeah. It’s a classic. Yeah, I mean, and I think that one can also be aligned with a given medium or a way of expression at any given moment and not at others. And I noticed that you used photography in some of your early work, the collage with the Gregory Crewdson photograph, which is, of course, funny, but yeah. So, did you have some affinity with photography and maybe that has changed over time?

Yeah. Yeah, I definitely did. I think what I like about photography is, unlike painting, it captures a moment faster. And maybe because it does that, it’s a more genuine moment. If it’s not a staged image, or even if it is. I am a people watcher person, I can sit in a park and just watch people. And I feel like photography also does that. And I was interested in, “How can I break up this idea of minimalist painting or whatever it may be with these everyday moments or these images that are photos?”

Also, I don’t study photo, so I’m also fascinated just by the technique in general. Yeah. I don’t know, photo’s hard. I started to read. People were like, “Read this theory book about photo,” but I haven’t gotten there yet, but there’s definitely an affinity to photo and being able to abstract an image, because I also have done woven pieces, where I weave this image that I found or that I took. And that idea that seems interesting to me too, abstracting an image. Yeah, photo, I’m still at the beginning of that.

Yeah. I mean, the only photography theory I still read is Camera Lucida. So, more Barthes, because photo’s theory, it’s a whole other realm that can be inscrutable in a weird way, but yeah. On this point about medium, again, I think it’s important to point out or to emphasize that you specifically bring up Julie Mehretu in your artist’s statement as well, and she’s such an interesting figure for a multitude of reasons.

I’ve been watching her from afar for a while, and she had this show at the Whitney, and I’ve been watching all of those videos. But I feel like the way she talks about her work is in relation to not only art history, but also events in actual history, and the way she’s able to place them into her paintings and also apply painting techniques to it. It’s a masterful thing that I eventually want to be able to get to a place where I can contextualize my work with historical events and historical painting.

It also brings up the question, the more art historical question of what is your relationship to abstraction?

Okay. Yeah. That’s funny. You mentioned this in the Queer Formalism, the second one. I used to be a figurative painter or drawer, and I always was interested in abstraction, but like many people, it felt like it was above me or something, or I was like, “Well, if I don’t get it, then I must not be able to make it.” But then I hit a wall with figurative drawing as a queer person and as a man, and trying to depict love with figures, I was falling into this trap of sex and showing all these things, and it never really left that world. And I was becoming frustrated with the critiques that I was getting. “Oh, this is about sex and maybe about love, but not really.” And I was like, “Okay, well, what do I do? How can I make it more about love?”

So then abstraction showed up and I was like, “Okay, well, how can I take the figure out?” And I just took it off slowly, slowly, and then it was just out completely, and then that’s where abstraction came. And then once I was reading this queer theory, I was able to understand how abstraction played a role in my thought process. I was reading queer theory and architecture in bath houses and clubs. That’s the origin of where my interests started. So I was like, “Okay, these buildings that were historically not used for these things are being used for gay sex.” And then I was like, “Okay, what is the foundation or the structure of this?” So that’s where I think it started. Take out the bodies and what do you have? And you have this building, but you have the red lights, and you have other things that can be painting things, like lines and color and space.

That’s really interesting, especially in the context of what you’ve explored in terms of directionality and direction, because so much of those spaces are about geography and being a destination of sorts, or even places like LA or New York or Chicago being destinations of sorts, in terms of race, in terms of sexuality, et cetera, et cetera.

Yeah. I didn’t think about this too much, but saying, because I did live in a city prior to being in Michigan and a lot of this work manifested when I was living in the woods in Michigan at Oxbow. I felt like I was able to take my mind out of, I mean, I was literally not in a city. So I just think it’s interesting that this work came out of isolation pre COVID, just living. And also, Agnes Martin has this saying, “If you can’t live alone, you can’t be an artist.” It’s very funny, but sometimes I’m like, “I kind of think she’s right.”

Yeah. She’s another queer icon for sure. But that’s a whole other conversation, but the ways in which queerness is marginalized in her work, but maybe as a final question. I was thinking about abstraction, and then I was thinking about these questions of direction, and it got me thinking, I wonder what your relationship to music is, because music is an abstraction of sorts. And it also has everything to do with direction, not only in terms of reading music, but also the conductor or the direction of the music to the listener.

I love this question. Oddly enough, like my art education, I was also trained classically as a clarinet player when I was growing up, and I’ve always been interested in classical music, but then as I got older, it’s still there, but the whole idea of having to perform this piece that’s written by, I don’t know, probably some white dude who’s dead or something, or not. But I became less into that, but I still liked order and music. I think I still have an appreciation for Stravinsky. I love him. And also, so this person that I love, Julius Eastman. Maybe he’s a gay, oh, is he? I think he is. Maybe I shouldn’t say that. He makes classical compositions, but they’re kind of a little off.

Sounds gay.

Yeah. And I think that’s the best way to describe my interest in art and music. There’s this classical structure, but it’s slightly off kilter. And you’re like, “Oh, this sounds like it could be a symphony, but it’s kind of not, or it’s kind of weird.” And you can’t pinpoint what is off. It’s just a minor, what is it called? A chord, or whatever, that makes it a little weird, but you have to understand the basics to fuck it up, kind of thing. So yeah, that’s kind of where music. I actually listen to music when I’m making work all the time. So it was probably in there, but yeah, that’s it. I mean, when people often are like, “This feels rhythmic.” Or I have this one piece that looks like a piano key and I didn’t even realize that, we were like, “Oh, this is a piano.” And I was like, “No, but I love that you thought about music and rhythm and structure.”